Improve and optimise your carbohydrate intake for performance.

Next, we move onto fueling performance with something I call the Max Energy System (MES), which aims to target nutrition for optimal sports performance for all levels of cyclists.

The underlying principle is simple: it's all about the carbs (you thought I forgot about them, didn’t you?)

It is now widely accepted that consuming a diet sufficient in carbohydrates, along with ingesting carbohydrates during and following exercise, can improve performance. In fact, carbohydrates don't have to be eaten in order to improve exercise performance. Just rinsing the mouth with carbohydrate solutions without swallowing has been shown to increase endurance capacity.

It is also well known that having a lot of glycogen in your muscles when you start working out is an important part of doing better.

A large part of an athlete's ability to train every day depends on how well their muscle glycogen stores are restored. This process needs a lot of carbohydrates in the diet and a lot of time.

Providing effective guidance to athletes and others wishing to enhance training adaptations and improve performance requires an understanding of the normal variations in muscle glycogen content in response to training and diet, the time required for the adequate restoration of glycogen stores, the influence of the amount, type, and timing of carbohydrate intake on glycogen resynthesis, and the impact of other nutrients on glycogenesis.

This lesson looks at how the latest research on glycogen metabolism in physically active people can be used in real life. This will give you a practical way to improve training adaptations and performance.

The typical athlete has 500-800g of carbohydrates stored in muscle glycogen and liver glycogen (a small fraction versus fat stores); this is enough to fuel 2-3 hours of intense exercise.

Most endurance athletes are familiar with “bonking” or “hitting the wall”; this is the point when carbohydrate stores become depleted, usually around 2-3 hours into an event. At this point, the athlete has only fat for fuel and intense performance cannot be maintained unless carbohydrates are consumed.

The MES has simple strategies that can delay or completely prevent this from happening. These strategies are making sure that you start with optimal muscle glycogen stores and liver glycogen stores and fueling during the ride or race using drinks, gels, and/or solid foods.

There’s also some assumed knowledge in this lesson.

Firstly, after a long sleep or many hours at work, your blood sugar will fall and it is likely you will be moderately dehydrated. Low blood sugar equates to low energy and dehydration will compound.

Secondly, an understanding of where different types of foods sit on the Glycemic Index (GI).

If you are unaware, the Glycemic Index is simply the speed or rate at which carbohydrates are broken down. Some of them are broken down fast and some are broken down very slow and there's a time to have slow-burning carbohydrates and there's definitely a time to have fast-burning carbohydrates.

The glycemic index scale is a ranking of 0 to 100 and 100 being glucose. It's the fastest to exit from the stomach into the blood supply of all the foods hence that gets a score of 100. The slow-burning carbohydrates are whole foods with lots of fibre in them. Think of oats if it is breakfast time, or think of most fruits. Fruits tend to be low to medium GI.

It is important to maintain hydration.

Whenever you sleep you get dehydrated and when you wake up the morning your urine is going to tell you that there is a modest or maybe even extreme amount of dehydration. How you tell that is just by the colour of that first urination in the morning.

You want to get back on to target urine colour as soon as possible. And the easiest way to do that is to wake up and go straight to the bathroom and check the colour of your urine.

You will find a urine colour chart below.

Then the first thing you do after that is drink 500ml of water. And the reason you drink 500ml of water is that firstly it is going to get your rehydration back on track.

500ml is enough to overload the kidneys so that within the next 30 to 45 minutes you have to go to the bathroom again. And that means you have another opportunity to check your urine colour.

The main takeaway is that maintaining hydration by drinking water and checking the colour of your urine until you ride is simple and important.

This urine colour chart is a simple tool you can use to assess if you are drinking enough fluids throughout the day to stay hydrated.

Ideally, urine should be pale yellow or ‘straw-coloured’.

This colour once identified on the Urine Colour Chart corresponds with a state of optimal hydration. The darker the colour, the more concentrated the urine and the more dehydrated you are.

Be aware: If you are taking single vitamin supplements or a multivitamin supplement, some of the vitamins in the supplements can change the colour of your urine for a few hours, making it bright yellow or discoloured. If you are taking a vitamin supplements you may need to check your hydration status using another method.

Carbohydrate Loading or carboloading is an eating and training technique used to build up high reserves of glycogen in muscle fibres for performance in endurance events. The big question is does it still work? The answer is yes, carb loading still works. This part of the guide uses two well-known papers, found here and here.

Here is what we know about carboloading.

Glycogen concentration in the muscle is dependent on the athlete’s diet. More carbohydrate equals higher glycogen stores. Glycogen concentration declines during exercise, especially higher intensity exercise. Higher glycogen concentrations in the muscle have resulted in less fatigue and better performance.

It was originally thought that you needed to deplete the carbohydrate stores in your body for a few days, and then start carb loading, creating a higher than normal level of glycogen. While your body does replete glycogen faster if you have fully depleted the stores, it does not bring them up to a higher level. In other words, your glycogen stores fill up faster if you’ve been fully depleted, however, they do not fill up more than if you had not completely depleted them.

This style of carb loading created athletes that felt weak and irritable, due to the lack of carbohydrates providing energy. A taper strategy became more popular as you got closer to your event, you trained less and consumed more carbohydrates. This works well and took about 6-7 days. Eventually, a 2-day program took over and this seems to be the most prevalent way of carb loading in the 2020s, and the one that we use.

Simply put, carb loading is shifting your diet towards carbohydrates for 48 hours before your event, leaving the fats and proteins off of your plate. Ideally, you don’t overdo it with tons of fibre that can create gastrointestinal stress, but some fibre is good to keep things moving through the body.

Before any intense training session that will last over 3 hours. When you go on a long ride, make sure you have carb loaded so that you have glycogen stores that are topped off and ready to attack the long duration. Also, before any big race. Especially during stage races when you really can’t eat too many carbs.

Carb loading is defined as 5-12g of carbs per kg of body weight. From experience 6-9 g per kg of body weight 2 days out, and then 8-10g per kg of body weight the day before the event is best. If you don't want to be strict and count your carbs, think about it as shifting your diet towards carbs and eat a little extra.

When choosing carbs for cycling include rice, bananas, sweet potatoes, oatmeal, bread, and pasta. Test the best type of carbs for your body on your next long ride. Good carb loading foods include fruit, oatmeal, rice, bread, sweet potatoes, and rice.

While processed foods are easy to use for carb loading food, they aren’t the best carb loading foods in terms of quality. Make sure your digestive system can handle all the fibre before you go overboard and try only to use fruit as your carb loading food as an experiment.

Weight gain: for every 1g of carb you retain 3g of water. This will create some weight gain, but it will come off as you race. The benefit of having carbohydrates to fuel your racing and exercise are well worth the slight gain.

After eating big carb meals, aside from feeling unusually full you will also feel tired. We have all had that feeling where, after a large meal, the number one option is to find somewhere quiet and lay down for a while. Lethargy is actually a natural part of the digestion process, forcing us to reduce our energy expenditure post-meal.

Of critical importance is just knowing that this is a natural process and these feelings of fullness will translate into a fully loaded liver and muscle glycogen stores.

While you may not always carb load for every long or intense workout, shifting your diet towards carbs can help periodise your carb intake for normal training days. This is when you want to utilise carb loading foods like pasta, fruits, bread, etc. So if you have high-intensity intervals the next day, anything at threshold or above, you’ll want to make sure that your glycogen stores are filled and ready to crush the workout.

Shifting your diet towards carbs simply means focusing on eating carbs over protein or fat the day before the hard intervals. You don’t need to go crazy and carb load for this workout, but make sure the glycogen is topped off. Even adding in a carbohydrate-heavy snack before bed will help.

Staying topped off on carbs for long, high-intensity sessions, will allow you to perform at your best in training. Next, we are going to focus on what to eat the day of important training or race days.

The food you eat before your ride is dependent on the duration and intensity of the training ride. The information from this part of the guide comes from Rothschild et al. 2020.

The goal of these pre-training interventions is to optimize both training adaptations and acute performance during key training sessions. We have already learned that high carb availability is an important part of this. But here we are going to set protocols for periodising the intake of carbs.

From the standpoint of practical application, the duration and intensity of the exercise session should be considered when considering the best pre-exercise nutrition choices, along with your personal preferences. This is because performance is improved following pre-exercise carbohydrate ingestion for longer but not shorter duration exercise.

The duration and intensity of the session should be considered when considering the best pre-ride nutrition choices.

Before shorter duration rides that focus on lower intensity steady-state efforts, it may be beneficial to withhold carbs, while there is little evidence supporting carb restriction before high-intensity sessions.

When consuming less than ~75 g carbs, food choices before HIIT can be left to personal preference.

For longer duration rides (>90 min), there is little evidence to suggest fasted-state training offers any additional benefit, although this is still practiced by approximately one-third of endurance athletes. Ingesting less than ~75 g carbs is unlikely to impair mitochondrial signaling adaptations from longer-duration, low-intensity rides while consuming 75–150 g carbs prior to extended high-intensity sessions is suggested to increase endogenous fuel storage.

Now that we have an idea of the number of carbohydrates needed here is an example for a race day or hard and long training ride. We are aiming for a meal that contains between 75 to 150 grams of carbs.

Breakfast is the biggest meal of the MES and is ideally eaten 4-3.5 hours before the start of the ride. The reason it is a big meal is, just like your hydration, your energy levels have dropped overnight. So blood sugar is going to be really low and breakfast reloads your blood sugar and the energy that is inside your liver.

The liver can hold up to about 0-160 grams of glycogen. But those glycogen stores are labile, which means it's mobile. You are using your liver glycogen quite readily in normal life and you will use liver glycogen on big rides.

When you sleep you can drop down to about 10 20 30 grams of glycogen, so you want to have breakfast that has a carbohydrate base and a good mix of low GI foods.

Note: While the glycemic index appears to have only a small impact that is more likely to be observed in time-to-exhaustion, but not time-trial performance tests.

The liver can be topped all the way up within two hours and that's very different from the other stores of glycogen in the body which are actually inside your legs. If you miss a magic window of opportunity to reload muscle glycogen, they can take 12 to 24 hours, sometimes more to reload those stores. A big breakfast has to have a good mix of low GI carbohydrates loading blood sugar and loading your liver.

What this liver loading meal actually consists of will vary from person to person and their preferred tastes.

To give you an idea of the amount of food involved here,

• 1 cup low fat muesli

• 1 tub low fat yoghurt

• 1 tablespoon of honey drizzled over yoghurt and muesli mix

• Mixed berries stirred through muesli. About ½ to 1 cup of whatever berries were available

• 2-3 thick slices of bread, toasted with jam or honey

• 1 medium banana

• 250-350ml of either apple or orange juice

• 1 espresso

This is a lot of food but we aren’t done with pre-ride food just yet.

The next step in this process takes place one hour before exercise with the aim of a blood sugar top up. Three hours after eating our big breakfast you are on a downward side of the blood sugar curve.

You have already reached your Peak blood sugar concentration and now you are coming down just a little bit. If you were to get on the bike you could feel a little bit flat in the first stages of the ride, but definitely after an hour feeling very flat because you have used up most of our blood sugar just in resting.

One hour before you get on the bike have a small low GI snack. We want something small that is going to burn nice and slow. So that when you do get on the bike, hopefully you've timed it to reach the peak of that digestion or that GI curve of that snack. And an ideal snack here is a medium sized banana.

The textbooks will tell you it's 20 to 25 grams of low GI carbohydrate for this blood sugar loader or snack and that just happens to be exactly what's wrapped up in a banana or a little muesli bar.

And that’s it - you are ready to ride an hour after this blood sugar top up.

But this time period also comes with a warning. And it’s this - at this point you may be tempted to have another top up of some sort, whether it’s some sports drink or a gel. But if you’ve followed the steps correctly you don’t need it. There is some fear of hypoglycemia from consuming carbs between 30–60 minutes prior to exercise; however, despite occurring in a small number of cases, there does not appear to be any detrimental performance effects or any relationship between low blood glucose concentrations and performance.

It is better to experiment here because you might be one of the small cases of rebound hypoglycaemia.

To explain rebound hypoglycaemia in physical terms, you're on the start line and you feeling tired like you feel really really slow and sluggish and this happens a lot and it can be rebound Glycemic and what that means is that you've had a good mix of carbohydrates in the lead-up to your event and you overdo it with the wrong mix of carbohydrates and what happens then is there's a trigger sent to the brain saying hey, there's so much blood sugar inside this person's system we've got to push some of that out otherwise, there's going to be problems.

So insulin is released and those good feelings and good energy you had from maybe a perfect 3.5 hour meal and maybe a perfect one hour pre-exercise snack all of that can be undone by a fast-acting carbohydrate coming in over the top and triggering insolent. And as soon as that happens the blood sugars washed out of your system, that's a metaphor, but nevertheless. And that's why you feel really tired at the start of a ride.

You want to avoid that.

After loading the muscles and liver with carbohydrates you are ready to ride. If you had low GI carbohydrates you will experience a nice stable peak. It's more than enough energy to get you through the first 45 minutes to 1 hour of a ride. In that time you are going to be burning the sugar that is inside your blood that has come from that very careful pre-ride nutrition plan. However, if it's really intense at the start of this ride for the first 30 minutes you are going to burn through more blood sugar than you normally would.

So there are two reasons why it is safe and also desirable to reach for some fast-burning fuel after 30 minutes.

Number one is that because you have hit the accelerator so hard it will chew through the blood sugar you had and point number two is that the hard intervals or sprinting for traffic signs and then the big climb you might have in the middle of that 30 minutes has triggered the release of what is called catecholamines.

We don't need to go too far into catecholamines but so long as they're released or as long as you've done some hard efforts. It's then totally safe to take on board some fast-burning fuel.

Your carbohydrate intake during the ride is dependent on the duration of your ride. No matter the duration of your ride, there are some things to keep in mind. For example, you don't need any slow-burning foods.

Also, it is important to realise that any foods (bars, gels, chews or others) need to be ingested with sufficient water to make sure gastric emptying is fast and no stomach problems develop.

No food is needed if the ride is less than 45 minutes in duration. There is no need to take in any carbohydrate. There is little or no evidence that carbohydrate intake or a mouth rinse does anything. It may not harm, but there does not seem to be a need.

When the exercise is a little longer and is “all-out” for that duration, performance will benefit from either carbohydrate intake or a carbohydrate mouth rinse. What is best depends on the practicalities of ingesting carbohydrate. Sometimes it is easier to simply rinse and sometimes it will be just as easy to swallow the carbohydrate solution. The types of carbohydrate does not seem to matter much here.

A note on why, what and how of carbohydrate mouth rinsing. If you are in the initial phase of "training low" and not yet adapted fatty acid oxidisation during rides, carbohydrate mouth rinsing how been shown to not impair performance. Many studies since the 2004 James Carter et al. study have shown that carbohydrate mouth rinsing can improve performance when compared to a taste-matched placebo or even water.

The most common protocol is the 5-second mouth rinse in regular intervals where you must spit out the drink afterwards. Other studies have tried to set a dose-response effect of longer rinse duration of 10, and 15 second mouth rinse, but the limit so far appears to be on the 10 second-rinse VS the 5-second mouth rinse protocol. Caution should be exercised with rinsing for more than 10 seconds as suggested by Gam et al. (2013), since longer durations might affect normal breathing patterns and impair performance.

You can interchange a 10-second rinse with a 5-second rinse depending on how intense you are breathing. Light breathing, a 10-second rinse works, when you are breathing is a little bit more heavy, try and guarantee at least the 5 second window or postpone the mouth rinse for a couple of minutes later, when the intensity lowers a bit. The ideal condition would be to rinse every 5 to 10 minutes for the first 60 to 75 minutes of the ride.

The liquid does not need to be a specific isotonic drink mix but adding table sugar at a concentration of approximately 6% (30g of sucrose to 500ml of water) is a cost-effective option.

For exercise lasting 1-2 hours, some carbohydrate has been shown to improve performance and 30 grams per hour is probably sufficient. With increasing duration, it is recommended to increase the intake up to 60 g/h.

At ~45 minutes you can begin taking on your first in-ride fuel and the general rule of how much you should have is 60 grams of carbohydrate per hour and there's a reason for it. It's just what your system can handle and that's the the easiest way to say it. What that means in technical terms is that when you're taking a blood glucose, let's just say from from gels. Glucose is handled by an enzyme called SGL T1 that enzyme can only handle 60 grams of glucose per hour. So you could just give it double or triple that it just won't be processed. It just backs up in the gut and you'll feel sick.

If the intake is not higher than 60 g/h any rapidly oxidised carbohydrate will work (glucose, sucrose, maltodextrin and some forms of starch). When the intake is higher than that, it is recommended to use carbohydrate mixes that use different transporters. The current evidence based ration is 2:1 glucose:fructose.

As a reminder, if you are fully loaded before you start riding you don’t need to start eating before say 45 minutes into the ride. If you do start eating earlier you run the risk of rebound hypoglycemia. The only reason you could and should eat before 45 minutes is if there was some intensity in the first 45 minutes because even if you are close to fully loaded with fuel, you will be protected from rebound hypoglycemia because the intense effort released catecholamines.

At ~45 minutes you can begin taking on your first in-ride fuel and the general rule of how much you should have up to 60 grams of carbohydrate per hour. There appears to be a dose-response relationship and higher intakes are recommended as long as this does not cause stomach problems (or other gastrointestinal distress).

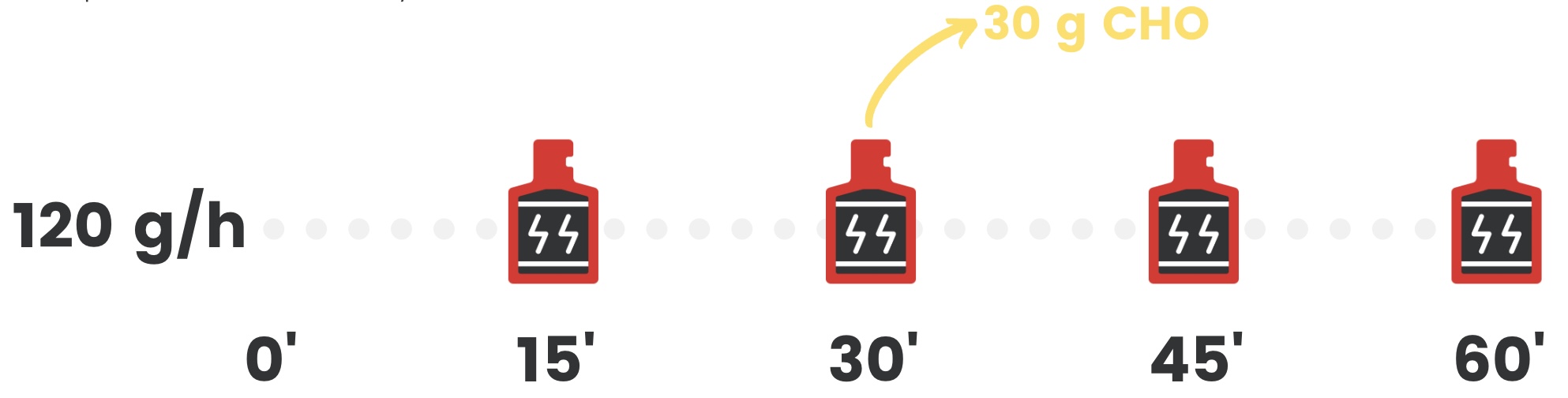

Now we are getting into a much larger amount of carbohydrates per hour. We are talking >60g/h up to 120g/h. The way you get to >60 g/h is through a different door. So the SGLT1 sits in the small intestine and that's great because the glucose from the gels coming down to meet it then just rolls around and passes it on to the blood supply as long as it's under that 60 gram barrier, but there's another doorway to get carbs into the blood supply. The enzyme that handles fructose and that enzyme called glute 5 which allows 30 grams of fructose into the blood. So you can get 60 grams through on glucose and 30 grams through on fructose. You can get a maximum of 90 grams of fuel into your blood supply.

How you do this is up to you. You can get there through one gel and half of a bidon of sports drink. You can drink a whole bidon of sports drink if it's mixed up the right way. You could have two gels one every 30 minutes and wash it down with water.

To take this further, we are now seeing the possibility of a performance benefit of even more than 90 g/h. A new research paper published by Virbay and colleagues (2020), highlighted that mountain marathon runners absorbed a very high dose (120g/hr) of carbohydrate from a 2:1 Glucose:Fructose formulation and experienced little to no gastric upset in a real-life race-paced mountain marathon event.

Prior to this event, all 26 elite/professional mountain marathon runners completed a 3-week bout of nutritional training, where the athletes would complete their weekly training commitments. During this time they added progression by increasing the amount of carbohydrate consumed within each training session until they found themselves comfortable at ingesting 120g of carbohydrate per hour.

The results demonstrated that during the event, the athletes that consumed 120g/hr found the event significantly easier, statistically compared to those fueling on 90g/hr and 60g/hr respectively. Another key finding was that biochemical markers of muscle damage in the 120g/hr group were significantly lower than groups consuming 60 – 90g/hr. This highlights that muscle fatigue is likely to have been reduced, offering the stronger potential for exercise performance to be maintained during long-duration events, but also holds significance for races where limited periods of recovery are key to the race outcome, such as multi-day stage racing.

Of course, this research is very much in its infancy and it will certainly take time for this area to develop and for further studies to assist in defining clearer answers on whether up to 120g/hr may be possible if combined with a gastrointestinal training regimen. It’s important to remember that the intestine is a trainable organ. We have created a guide and protocol to train your gut over a number of sessions to accept this level of carbohydrate intake.

At this point in the guide, we have covered all the evidence-based recommendations, especially the idea that all you need on the bike is high GI foods and that it’s better to eat just enough to get you through to your next snack and it could be every 30 or every 45 minutes and it's not the heavy stuff.

There are some exceptions here that come from professional cycling and this is where a little bit of old-school mixed in with science is one really important exception to the high-GI rule. And it applies to all riders doing longer than 3 and a half hour rides or races. That is to take on board an energy sink. These can be any whole foods such as pastries or it could be something like a small Nutella or peanut and jam sandwich. This introduces some fat and some protein into your system and this doesn't work for everyone and it does take a bit of time getting used to but this is definitely a pro World Tour tip and most guys do it.

What the energy sink does is it burns slower throughout the back end of your exercise session or race and allows you to put some more fast burning fuels on top and have that slow burn blood sugar come through and possibly take up most of the energy requirements.

It's especially helpful to drip feed through if you can't get to a gel or if the race is too intense for you feed yourself properly. So there is one exception to the general high GI rule during exercise. And that is the energy sink. If you're going over three hours of over three and three and a half hours up to five five and a half. So it's a good tip just to keep back up.

This section covers nutrition for recovery - or what to consume after training and racing. This guide follows a three-step process for post-ride nutrition.

Consume 60 g of glucose immediately after stopping the ride. Keep the glucose supply next where you store your bike and consume the glucose before taking your bike helmet off. The glucose could be a form of glucose lolly such as gummy bears or it could be a sports drink. You can buy a hundred percent glucose powder. The idea here is to consume them fast as you can because there's a stopwatch on because of the enzyme is GLT-1.

Then you can take off your helmet and go inside and start to clean up. Have a drink of water if you're sweating. You may even have a shower at this point or you may want to just sit down and have the stretch whatever.

The idea is that once you've taken on that board that glucose give it enough time to go through your stomach and hit the blood supply. Don't interrupt this process by putting any other nutrients on top. Just let the glucose go straight through your stomach and that will take about 20 minutes because it's a high glycemic index food.

Blood sugar curves that play based on that glucose standard shows that high GI carbohydrate should hit the blood supply after 20 minutes. It doesn't survive in the stomach. It goes bang straight through SG LT1 that enzyme that doorway and then it's into the blood supply and once it's in the blood supply we can do the second part of recovery, which is protein.

The timing and type of glucose are directed by this review.

The next step is done 20-30 minutes after the last step. Have a protein drink with 25-30 g of protein - this is a powder mix. It's just a matter of finding one that fits your budget and your taste. If you can do the glucose let that go through the stomach then get onto the protein.

The reason protein is so important is because you're breaking down muscle tissue. So you need some amino acids to come from the diet or your protein drink to start repairing those. Outside of that amino acids are used in the formation of capillaries. We're putting these superhighways all the way through our legs. So as we can get oxygen down to the furthest finest farthest corners of the muscle so that they can then take that oxygen and generate energy. And then we need a nice capillary network to get the byproducts back as well. So capillarisation of muscle and the amino acids that go into creating Those capillary reserves are really important.

Then outside of that, the endurance athlete is a chemical animal. There are all these chemical processes going on in these enzymes to converting this to this and from that to that. The enzymes responsible for clearing lactate, the enzymes responsible for moving oxygen along certain pathways, the enzymes responsible for most parts of the energy contribution, and the waste distribution parts of exercise are huge. And amino acids are used in the construction of enzymes as well.

So that protein drink is providing amino acids for a very important four-hour window after exercise. And that is the transcription and translation of genetic material that's going to build a certain class of enzymes depending on the training session you just did. If you did low intensity, then oxidative enzymes, if it was high-intensity the call goes out to start producing more in enzymes that deal with lactate clearance. So depending on the exercise, you'll get your custom-made enzymes, then you've got the capillaries and you've got the muscle as well. So there are really strong reasons why that protein drink is really good and it's such a simple thing to do.

This information is disused in further detail here.

And finally, it’s a matter of waiting another 30 minutes for the protein to go through and then having a mixed meal. Do not delay this post-exercise meal for more than three hours. This meal should contain a combination of carbohydrates, about 20g of protein, and some fat. And you are ready for the next day...